This blog is totally non profit-making. As a retired psychotherapist with 30 years’ experience, I write both for my own self-expression and to help others. If you value my posts, I would much appreciate you showing your support by becoming a follower of waysofthinking.co.uk

Judith Carlin at Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons

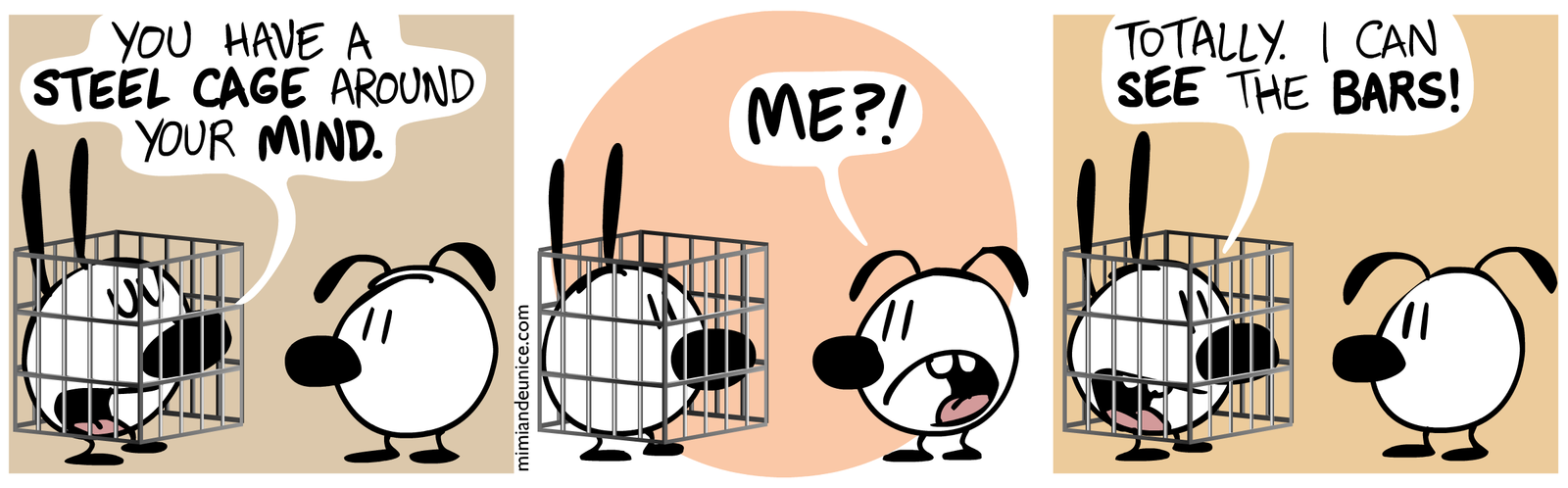

Sometimes, without our conscious awareness of the fact, we are our own jailer. We may be a prisoner of our thoughts, even though it may not feel as though we are.

What do I mean by this?

Ways of thinking that we have absorbed or inherited long ago may have become so much a part of us that we do not realise how destructive they are. Confined within a labyrinth of thoughts and feelings, we can experience being stifled and lost, lonely, trapped within our own skin. We may also be blind to our personal ‘caged thinking,’ and even attribute this to others, denying it in ourselves.

Mimi & Eunice, “Steel Cage” 2011. Wikimedia Commons

Mimi & Eunice, “Steel Cage” 2011. Wikimedia Commons

“The moment you say that any idea system is sacred, whether it’s a religious belief system or a secular ideology, the moment you declare a set of ideas to be immune from criticism, satire, derision, or contempt, freedom of thought becomes impossible.”

Salman Rushdie

Here are just some of the many ways in which we might be imprisoning ourselves with our thoughts:

- Inflexibility

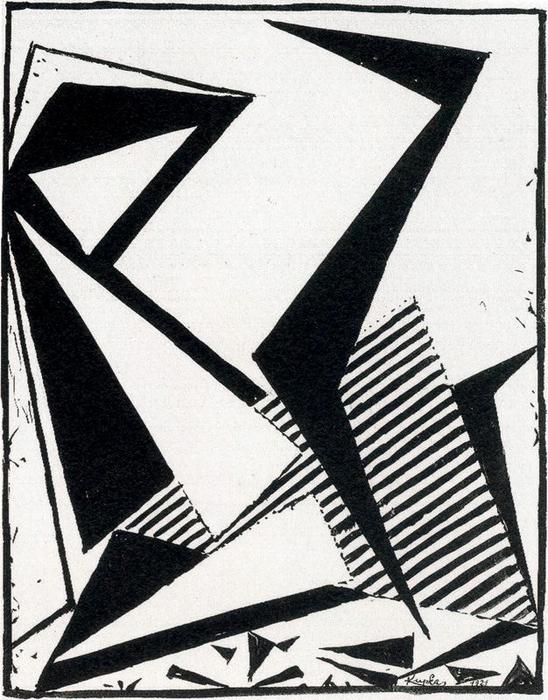

Being rigid and inflexible will mean that we are unable to adapt to change. It implies that we see the world in extreme ways, in all or nothing terms; there are no in-between areas or shades of grey. This will lead to an absolutist approach to life, one that will result in a limited, black and white, static and bigoted mindset.

Study in black and white 1 – Frantisek Kupka. 1924. Wikioo

This is the ‘I’m always right” approach, where there is a conviction that “only I, and only those who think just like me, are on the right path, and I can show others the way…my way.” Such a life is full of polarisations, of ‘either/or’ attitudes, of binaries, rights and wrongs, and it lacks room for doubt or shades of grey.

This uncompromising thinking style renders us woefully unprepared for the uncertainty and unpredictability of life. The formulaic nature of such ways of thinking leads to an immovability, a manner of asserting one’s views that brooks no contradiction, no possibilities, no ambivalence, no discussion, no choice.

We will, quite literally, be trapped in the prison of our mind. There will be an overarching sense of disappointment with life and with relationships; inevitably, we will lack the ability to feel real joy.

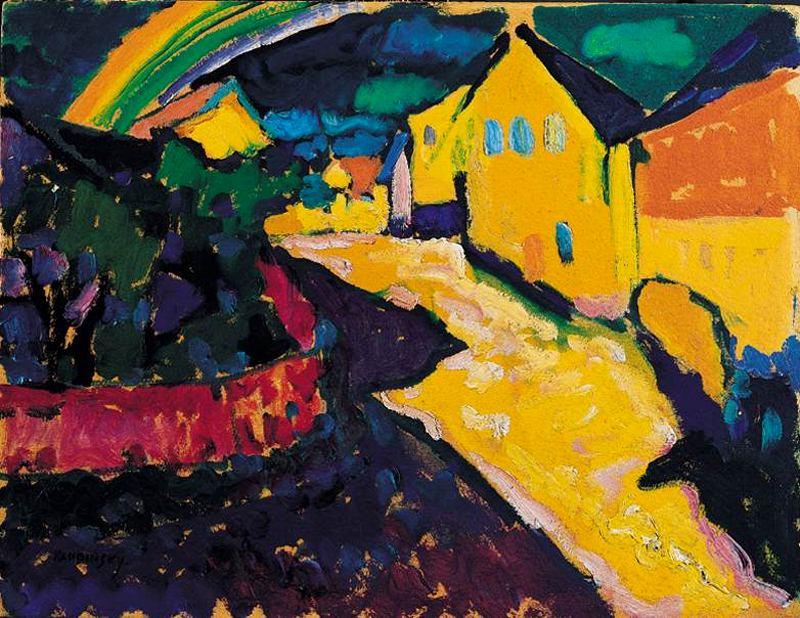

Murnau with Rainbow – Wassily Kandinsky. 1909. Wikioo.

Murnau with Rainbow – Wassily Kandinsky. 1909. Wikioo.

“When you reduce life to black and white, you never see rainbows”

Rachel Houston

- Imprisoning others…or trying to

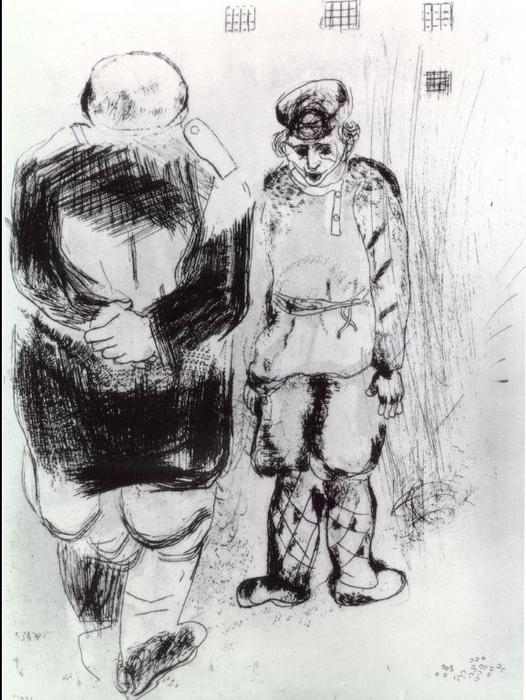

A man without passport with policeman – Marc Chagall. 1923. Wikioo

“Isn’t it crazy that another country is so close, and yet we can never go there because we’re not allowed? But it’s all land. I mean, men created the border, not nature. Nature doesn’t discriminate. Men do. It’s like we’re boxed in, but we do it to ourselves. We imprison each other with lines and boundaries instead of just letting people be free.”

Rebekah Crane, The Infinite Pieces of Us

This quotation can be interpreted on many levels. It may, of course, be taken literally, as it expresses an opinion of great value, or it may be seen as referring to ourselves, and the way we create some unnecessary boundaries in our lives.

With outdated or over-rigid rules, with our psychological fences and steel cages, we stop others from being free; those who are accepting and hospitable to others are often denounced and criticised.

Hospitable behaviour has traditionally been seen as a noble quality, an indicator of a generous and civilised culture. However, this image of hospitality has been eroded and, in our contemporary society, the forbidding forces of exclusion, discrimination, hatred, racism and rejection are revealing their ugly face.

Whilst, of course, there are times when we do really need fences and boundaries, how often do we erect them for ourselves and others when they are not truly necessary?

At an external level, we share the world with others; it is not ours to own or claim. Thinking that we ‘own’ our country, or our national identity, exclusively, is a myth. Instead of thinking in terms of creating outsiders and building fictional divisions, it is important to contemplate commonality.

We need to make boundaries between self and another more elastic, translate across vernaculars, offer greeting, help, welcome, invitation. We need to practise creating spaces to meet, rather than devising methods of exclusion. This mindset will obviously free us too, from old, outdated prejudices and fixed ways of thinking.

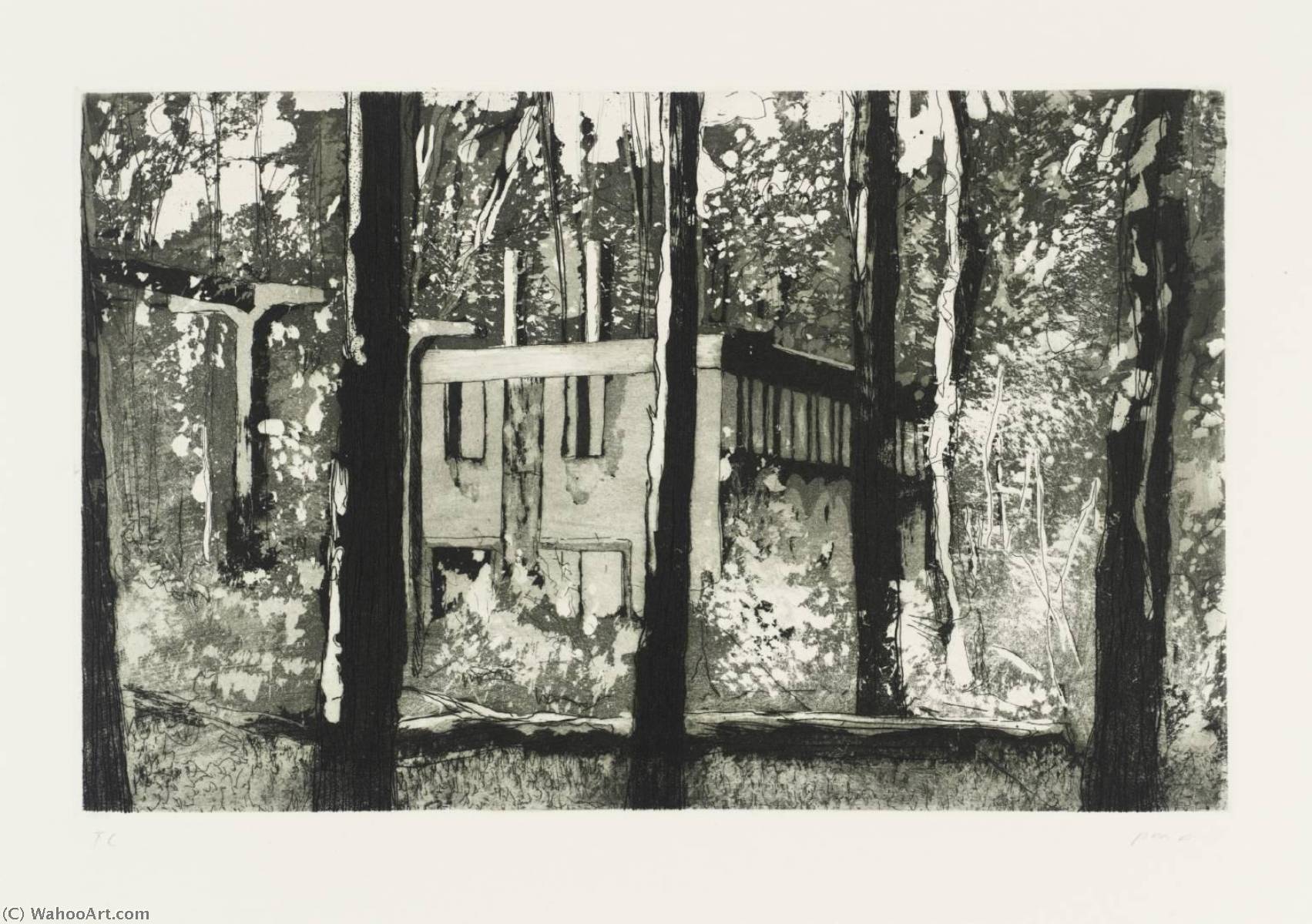

Border House – Peter Doig. 1996. Wikioo

Border House – Peter Doig. 1996. Wikioo

“You’re probably surprised to find us so inhospitable,” said the man, “but hospitality isn’t a custom here, and we don’t need any visitors.”

‘If this quotation from Kafka’s Castle seems strange to us, it is because we cannot believe that there is a culture, a society or “a form of social connection without a principle of hospitality. But what is left of this principle of hospitality today, or ethics in general, when fences are erected at the borders, or even “hospitality” itself is considered a crime?’

Gerasimos Kakoliris

Building barriers and being inhospitable are surely about wanting to control an uncertain world, both inside and outside of ourselves. Difference and diversity may threaten our own sense of identity and security, if it is shaky and uncertain. Perhaps we have not felt understood as children; then we may lack empathy and compassion as adults and shun those who might appear different from us.

Life is highly unpredictable, and learning to accept this incontrovertible fact is difficult. As a result, we may develop control-related tactics to try and ward off such uncertainty, like attempting to make the world, and other people, comply with our wishes. Thus we ‘box them in,’ subjecting others to our own inner constraints.

Some people try to deal with their inner chaos by creating order around them, outside of themselves. They may be attempting to render everything spotlessly tidy, washing and cleaning obsessively, having little conscious awareness of feeling messy, disturbed or ‘bad’ inside.

The energy for facing such inner turmoil is thus re-routed into frantic external activity. Their surroundings will be immaculate and orderly, but the internal world, lodged firmly in the unconscious, will still remain untouched, disorderly, chaotic. They will be out of touch with, and trapped by, difficult, unresolved feelings, which can emerge to disturb them both physically and mentally.

They are living unconsciously, unaware of the internal chaos that restricts their freedom. This compels them to conduct a fruitless and distressing routine of ‘tidying’ themselves inside by scrupulously organising their outer world.

If we rigidly limit awareness or expression of our inner feelings in this way, no matter how difficult they might feel, they will be unavailable to us to work on, either by ourselves or in therapy.

A flexible mechanism of regulation is required, not a strict suppression of such feelings, which, in itself, would indicate fear and uneasiness at the prospect of becoming ‘out of control.’ What we need to aim for is a sense of balance, so that we neither block off or imprison our inner ‘messy’ feelings with rigid internal defences, nor act them out destructively.

- Making things seem worse than they are.

Catastrophising is a terms that describes the actions of those who tend to make mountains out of molehills. Some things are, indeed, truly awful, and I am not suggesting that we should minimise our own or others’ pain. What I am saying is that we may need to try not to make situations heavier than they are.

“Everything hinges on how you look at things.”

Henry Miller.

Are you someone who makes mountains out of molehills, who catastrophises? If so, whether things are trivial or really tough, life will feel even more confined than it needs to be and there will be no space to think, contemplate, work through or reflect.

“The difference between a mountain and a molehill is perspective.”

Al Neuharth.

- The prison of depression

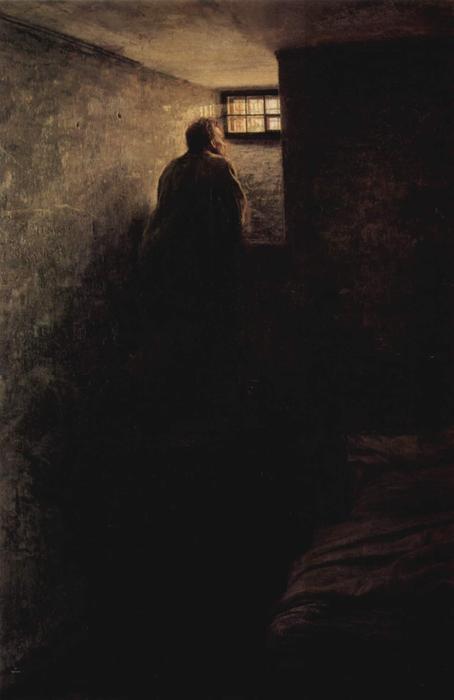

The Prisoner – Mykola Yaroshenko. 1878. Wikioo

“Depression is a prison where you are both the suffering prisoner and the cruel jailer.”

Dorothy Rowe

Being deeply depressed is, indeed, comparable to being in a prison, the prison of our own mind. Clinical depression is a serious and debilitating illness. It is much more than feeling sad. The depressed person cannot ‘pull themselves together.’ If they could, they surely would.

We should not underestimate how despairing a depressed person might feel, often hidden beneath a ‘cheerful’ persona.

“Minstrel Man

by Langston HughesBecause my mouth

Is wide with laughter

And my throat

Is deep with song,

You did not think

I suffer after

I’ve held my pain

So long.Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

You do not hear

My inner cry:

Because my feet

Are gay with dancing,

You do not know

I die.”

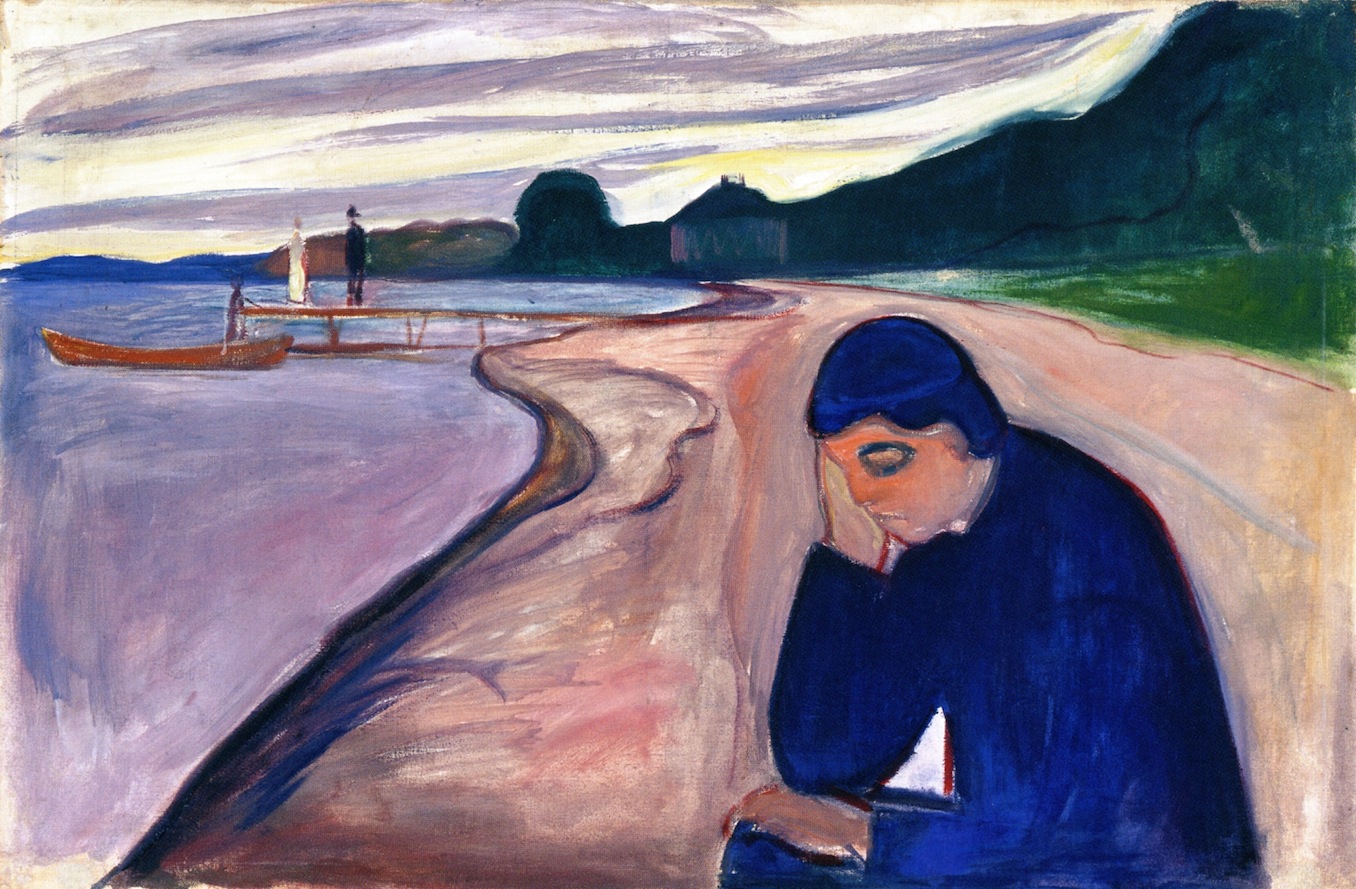

Munch. Melancholy. 1891. Wikimedia Commons.

Can psychotherapy help those who experience the hellish prison of depressive illness? The answer to this question is that it is possible to treat some people through psychotherapy. Obviously, there is no universal panacea, no magic cure and this treatment is not for everyone.

However, there are several kinds of psychotherapy which have been shown through research to help depression. A GP or therapist will make an assessment to help the person decide which modality might suit them. Many have found different forms of psychotherapy helpful.

There is a combination of factors in relation to the origins and causes of clinical depression; it has both chemical and psychological origins. Therefore treatment often needs to address both of these, in terms of medical or psychiatric help and therapy. It is up to the individual to decide, along with professional advice, which treatment or treatment combination may be right for them.

- Escaping the cage…

Anxious Thoughts – William Lee Hankey.(1869-1952) Wikioo

Anxious Thoughts – William Lee Hankey.(1869-1952) Wikioo

“I started to be free when I realised the cage was made of thoughts.”

Unknown

As the words above state, psychological freedom emanates from a realisation that we have created the mind-cage with our own thoughts. This means that we do have some control, although we may need psychotherapy in order to bring to consciousness the issues that are blocking our ‘escape.’

Which way to go? Which path to take towards freedom of mind and growthful self-knowledge?

Each person has to find their own path, their own way to freedom. No-one can make an escape for them, but others can help in indicating direction. Each person needs time and some kind of help, to change and grow.

Perhaps they will find a psychotherapist, psychologist, counsellor, guru, trusted friend or a group. Maybe they could try meditation, mindfulness, Buddhism, or other religions and philosophies.

Butterflies, Other Insects, and Flowers’ by Jan van Kessel, 1659.Wikimedia Commons

Butterflies, Other Insects, and Flowers’ by Jan van Kessel, 1659.Wikimedia Commons

There are many ways and many paths. Like the butterfly, we have to undergo a radical metamorphosis if we wish to fly free from the trap of our own body; we need to examine our stultifying beliefs and ideas, to ultimately escape the prison of our thoughts.

Hartwig HKD. Empty Cage Flickr.

“What I’m saying is you can’t do anything about the past. But it doesn’t really exist. Memories are just a mind manipulation to keep you tethered to something that’s no longer there. Free yourself and let it go.”

Rebekah Crane

© Linda Berman