Acrobat Falling. Everett Shinn. Wikioo.

Acrobat Falling. Everett Shinn. Wikioo.

“Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

Confucius

We all make mistakes, and therapists are no different in this regard. Learning from these mistakes is a crucial way of developing and refining our skills, no matter how experienced we may be. We can find examples of this learning from error through perusing the writings of many celebrated therapists throughout history.

Whatever our mistake, it is important to have awareness of what it might be about, and how it can reflect both the patient and the therapist. This can lead to more self-understanding for the therapist and, perhaps, further knowledge about the patient, or both.

For example, if we, as therapists, are talking more than usual, are we reacting to some internal pressure from the patient, to find answers, get it all right? If so, we will have learnt something valuable about the patient’s inner world. On the other hand, is the problem ours, in that we have have been late for work this morning and feel rushed? Such awareness on the part of the therapist, perhaps with the aid of supervision, is paramount to the therapy process.

Below are some examples of the kind of mistakes that therapists might make……

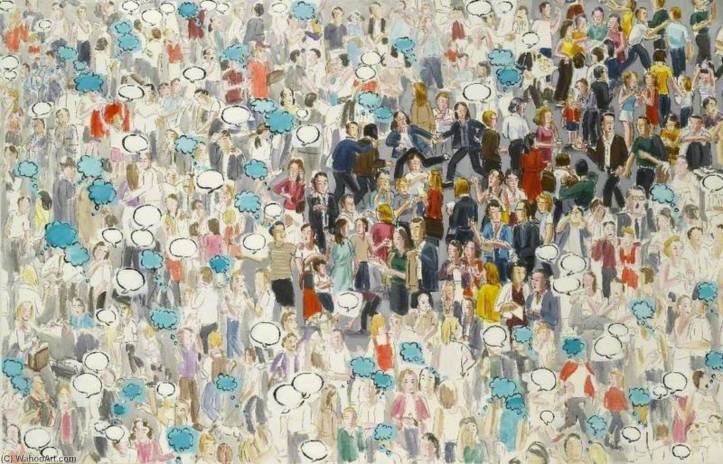

Talking. Margret Hofheinz-Döring, 1993. Wikimedia Commons

Talking. Margret Hofheinz-Döring, 1993. Wikimedia Commons

- Therapist Being Overactive

I was once writing some notes in a room next door to a therapist who had a particularly low, resonant voice. The therapist was seeing a patient. I could not make out any words, so confidentiality was maintained, but what I could hear was just a constant- and I mean constant- hum from the therapist. It sounded like there was no space for the patient to speak at all, no pauses, just a therapist’s monologue.

Over self-disclosure or too much talking on the part of the therapist means that the patient will not be the focus; there will be no space for reflection or reverie, no therapeutic silence, no ‘being with’ the patient, no mutual wondering and no waiting.

Practising being, not doing, is essential as a therapist; real empathy on the part of the therapist means that there will be no rush, no pressure, just a quiet and strong presence. An empathic therapist can be there for the patient without trying too hard to know how to help, to have all the answers or rushing into thoughtless activity.

Such ‘activity’ may take the form of over-interpreting or offering therapist-centred thoughts that are not attuned to the patient’s needs.

Instead, there needs to be a strong, implicit message of containment and confidence in the value of being there, quietly waiting with the other person for something to emerge from the unconscious that is more than a superficial statement or response.

Doing, Thinking, Speaking – Lisa Milroy. 2000. Wikioo.

Doing, Thinking, Speaking – Lisa Milroy. 2000. Wikioo.

“The alternative to being is reacting, and reacting interrupts being and annihilates.”

Winnicott

Allowing silent spaces can be so creative and productive, in our lives and in therapy. Such quiet intervals in psychotherapy allow the patient some space to feel free of therapist intrusion and over-activity.

If the therapist rushes into interpretation and quick ‘understandings,’ without waiting with the patient to see what might transpire, something valuable may be lost and the therapeutic process compromised.

Timing and pace are crucial in every psychotherapy session. Waiting with someone in an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion is crucial in this regard.

- Therapist Not Exploring The Here and Now.

“Nothing is more precious than being in the present moment, fully alive, fully aware.”

Thich Nhat Hanh.

Living in the present is not easy. It is difficult to stay with what is happening in the here and now, without allowing the mind to wander or worry and be distracted into the past or into an imagined future. This is also relevant to therapy.

The therapist needs to be highly aware of what is happening in the moment, in the room, between therapist and patient. ‘How does it feel, now?’ is a question therapists need to constantly ask themselves. Use of the therapist’s self in this way is a crucial part of the psychotherapy process, and shows us why Artificial Intelligence could not possibly replace the therapist.

Matt Brown. Eric the Robot. Flickr.

Matt Brown. Eric the Robot. Flickr.

“Emotions are essential parts of human intelligence. Without emotional intelligence, Artificial Intelligence will remain incomplete.”

Amit Ray, Compassionate Artificial Intelligence

Psychoanalytic psychotherapy uses the relationship between therapist and patient as an arena within which to explore sometimes self-defeating ways of being in relationships. Past behaviours will inevitably be repeated symbolically in the therapy relationship. When we are in therapy, it is likely that any relationship problems we have outside the therapy, most likely originating in the past, will be replicated in the relationship with our therapist.

The space between therapist and patient becomes a kind of ‘theatre,’ a stage upon which to reactivate and re-act parts of one’s past experience. Feelings and behaviours towards the therapist will inevitably reflect aspects of the patient’s primary caregivers. This is called the transference; it enables such issues to be highlighted in the here and now of the therapy situation, making them available to be worked through.

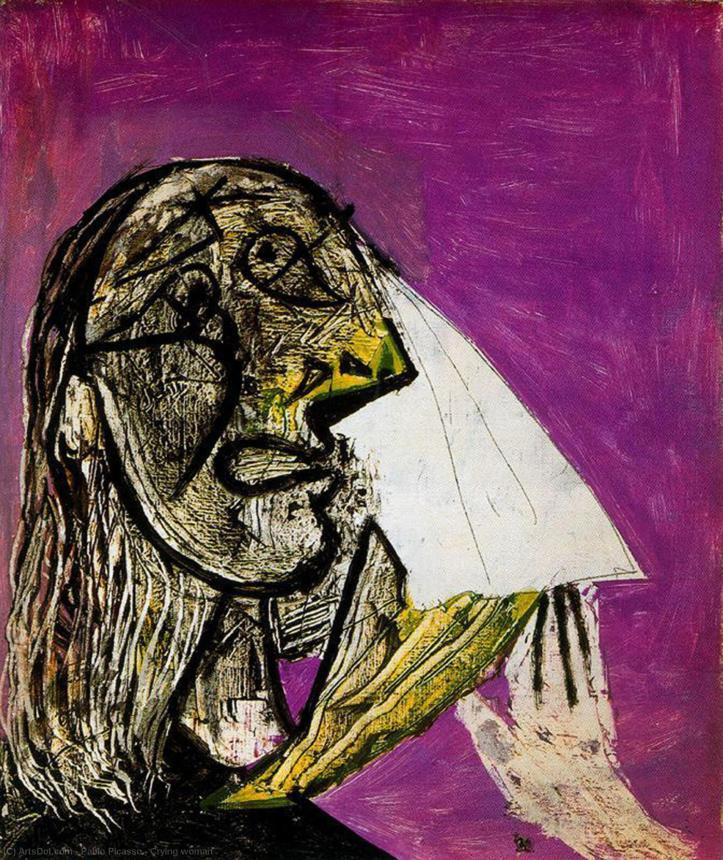

- The Issue Of The Tissue

Having a box of tissues on a table within easy reach of the patient is important. However, handing the patient a tissue when they cry may be interpreted in several ways. It could mean that you want to dry their tears, stop them crying, or that you do not think they are capable adults who can reach for a tissue without help. This could feel disempowering, giving all the power to the therapist for even a simple task.

This could also be regarded as over-nurturing, rushing to help and doing, not being, when what the patient needs is the therapist’s uninterrupted presence and focus. Being there in this way certainly does not imply watching a person cry in a cold and unfeeling way, but showing empathy and emotional care. It is about really being with the patient in their pain, in a quiet, safe space, with no sense of rushing or moving on.

Handing the patient a tissue could be experienced as an intrusion into the patient’s process, or perhaps it might convey that the therapist is not comfortable with tears. Getting up to hand over tissues, or leaning over to reach them, could be seen as closing things down, interrupting the process.

There may be different views about this, depending on the kind of therapy you offer. Yalom describes how the reactions to the tissues can be important and symbolic:

“Even the banal Kleenex box may be a rich source of data. One patient apologised if she moved the box slightly when extracting a tissue. Another refused to take the last tissue in the box. Another wouldn’t let me hand her one, saying she could do it herself. Once, when I had failed to replace an empty box, a patient joked about it for weeks.”

Yalom. The Gift Of Therapy, pp52.

Much more preferable than the therapist getting busy would be to use something like Yalom’s words in response to a weeping patient:

“If your tears had a voice, what would they be saying?”

Yalom, The Gift Of Therapy.

Crying Woman – Pablo Picasso. 1937. Wikioo

Crying Woman – Pablo Picasso. 1937. Wikioo

Part 2 of this post will be published next Tuesday. If you have found it helpful, do become a follower of waysofthinking.co.uk

© Linda Berman.

I find this very useful. I have just seen my first paying client and I am processing our session. Thinking back I felt I may have led them somewhat, meaning they spoke of fear of rejection quite a lot and this left me feeling this was a deep seated state from childhood, I queried their childhood and their memory was vague. I plan to take this to supervision

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad, Joan, that my post was useful to you. It sounds like a good idea to take this case to supervision. Thanks for sharing this and for your feedback to me. 🙏🤗

LikeLike

Thank you Linda. A thought provoking column – I am always seeking the balance in congruence and over talking.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on penwithlit and commented:

A considerable amount to ponder here. Some of these comments are in agreement with the considerable work of Betty Joseph.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you – and for the reblog. Haven’t read Josephs but will take a look! 🤗

LikeLike