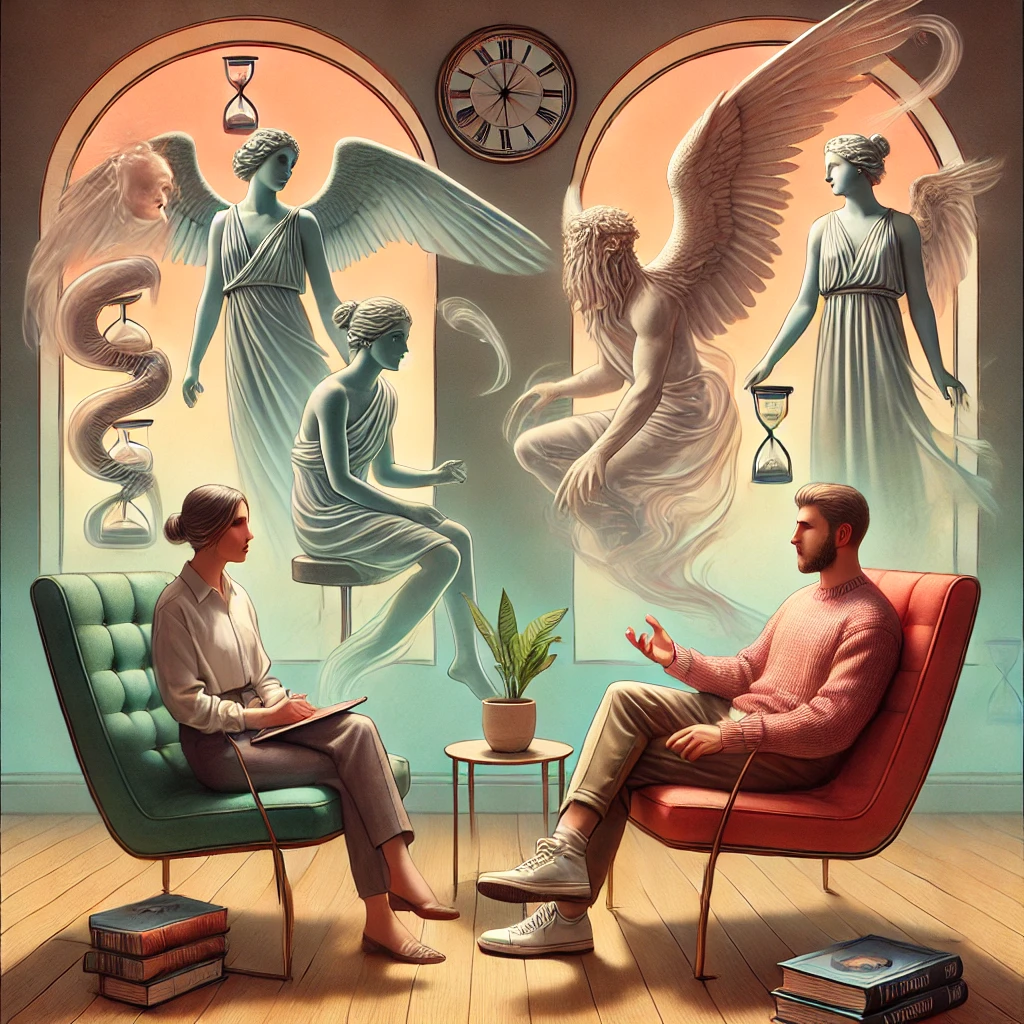

- Using myths and symbols in therapy

(AI Image)

“The meaning of a myth is to bring about a transformation, to bring the unconscious into consciousness.”

Marion Woodman

Myths and symbols play a considerable part in the therapy experience. The therapist needs to be acutely aware that beneath the surface of any client’s words there will be a rich mine of symbolic meanings. These symbols give potent clues as to what may be happening in the client’s unconscious mind.

In therapy, clients use myths and symbols in order to communicate difficult thoughts and feelings. A little like dreams, this use of symbolic words and phrases can soften the pain of some very disturbing thoughts, memories and experiences.

Overgrown Garden. Wikimedia Commons. 2009. From geograph.org.uk

Author Sebastian Ballard

For example, if a client tells the therapist that their garden is full of weeds, it’s messy, and overgrown and they just cannot cope with it any longer, there may be more than meets the eye to this statement.

Largely unconsciously, they are likely to be communicating verbal images that symbolically indicate deeper issues. With gentle exploration from the therapist, the client can be helped to make links to inner feelings of personal messiness, on an emotional level.

Perhaps life for them feels untidy, unmanageable, and unwieldy, like the overgrown garden. Symbolically, they have offered a deep insight into their life and their inner world, ready to be discovered beneath their story.

Myths also permit clients to discuss their problems a few steps removed, allowing a necessary distance. This is because communicating difficult events and disturbing feelings and memories through stories, myths and symbols, prevents people from becoming retraumatised by talking directly about painful issues.

The ancient Greek myth of Cassandra, is about a princess who was condemned by Apollo (for rejecting his advances) to be able to prophecy and warn correctly, but never to be believed. This myth could be used with those who suffered extreme trauma. Often they are not believed by others, who accuse them of inventing their story.

Nowadays, the term ‘Cassandra Syndrome’ is also used in psychology to described the frustration of, for example, the neurotypical partner of someone with autism, who cannot persuade others of the way in which they experience their neurodiverse partner.

Symbols themselves can be used to communicate difficult and intense emotions; they can help a client convey feelings that are not available to being expressed in words. In relation to art therapy, for example, aspects of the unconscious that are unavailable in any other way may rise to the surface when clients paint, draw, or sculpt their feelings.

One client * drew an image of themselves with a target tattooed onto their chest, as they felt they were always the butt of others’ insults and constantly getting hurt.

(AI image)

They had not been able to express their feelings in words, and began spontaneously to draw the image for me, which was highly emblematic of their inner vulnerabilities.

This powerfully symbolic drawing, similar in theme to the image above, enabled us to explore deeper implications. The client gained some awareness of how they unconsciously put themselves in dangerous situations where abusive others could aim emotionally barbed darts at them. With a traumatic past, they had very low self-worth, tolerating insults and feeling constantly victimised.

- Listening to the symbolism in the silence

Silence – Alexej Georgewitsch Von Jawlensky 1913. Wikioo

“Silence is one of the great arts of conversation.”

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Silences themselves may also be powerfully representative of what is happening internally for the client. They are heavily symbolic, signifying many emotions, replete with meaning.

In therapy, silences can be related to a multitude of feelings, such as sadness, disbelief, shock, fear, depression, grief, withdrawal, anger, or they can be a space for reflection, peacefulness, contemplation and the gaining of awareness.

To develop creativity and imagination, silence is also important. On the part of the therapist, making the space inside to listen to the silence in a deep, resourceful and thoughtful way can help the other person to feel really heard.

“The most important thing in communication is hearing what isn’t being said. The art of reading between the lines is a life long quest of the wise.”

Shannon L. Alder

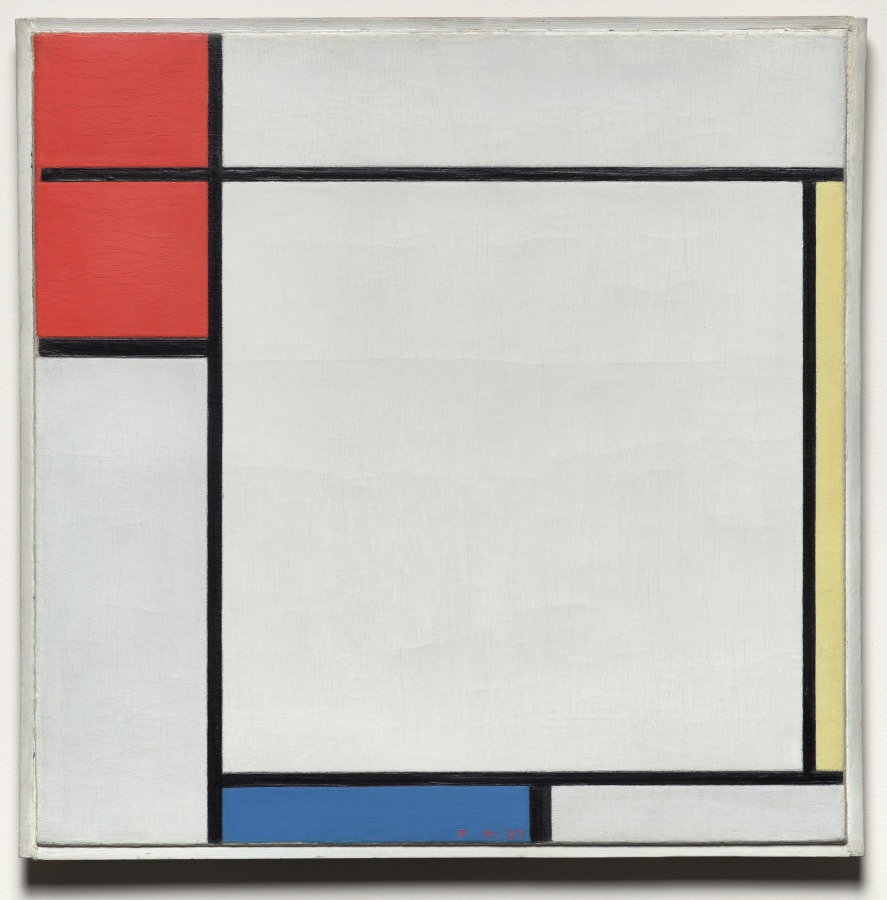

Mondrian. “Composition with Yellow, Red, and Blue” (1927) Cleveland Museum of Art.

“It is often the absence of something that gives a painting its power, the negative space that allows the subject to shine.”

Unknown

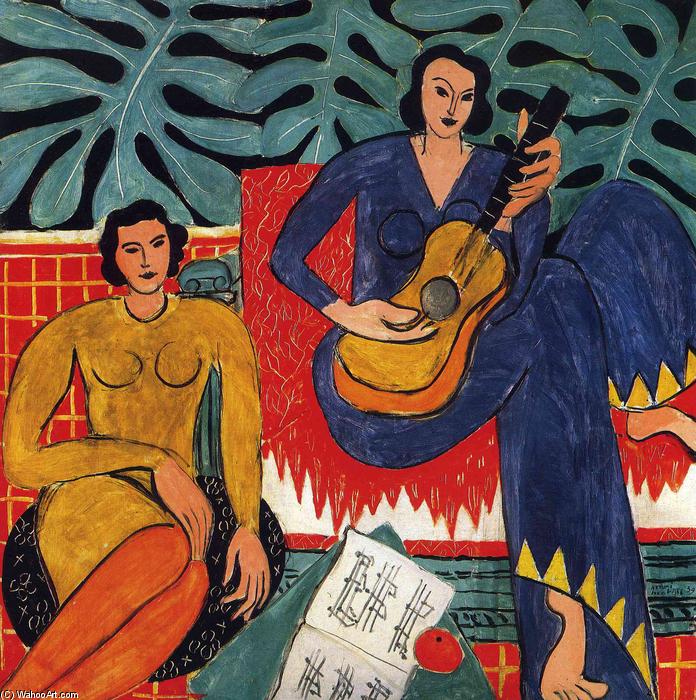

Music – Henri Matisse. 1939. Wikioo

“The music is not in the notes,

but in the silence between.”Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

As therapists, if we listen, really listen, to the silence, we will pick up all kinds of clues as to what might be happening for the client. As we can see in the Mondrian painting above, such silences may be compared with the spaces left in an artwork, without which the work would not be effective or meaningful.

If we can learn to listen to such silences, we will come to understand their symbolic meaning. Picking up visual cues from body language, expressions and gestures, is a kind of listening with the eyes. It is another way of reading between the lines, that is, interpreting the implied, unsaid message.

“He who does not understand your silence will probably not understand your words.”

Elbert Hubbard

The silent scream. Oil painting. 2013. Anichka Butenko. TakingITGlobal

“I’ve been screaming between these words. Did you notice?”

“Silence is the most powerful scream.”

Anonymous

Discerning symbolic meanings in the client’s words, silences and behaviour, will give the therapist a powerful insight into the other’s world.

It is also important that the therapist is well-versed in other cultures’ myths and symbols, as their meanings can differ dramatically across our pluralistic society. Being a culturally competent therapist will mean that they will be able to avoid making mistakes in terms of stereotyping people and making assumptions based on ignorance of the client’s culture. For example, a term that might be acceptable in one culture may be regarded as sexist in another.

Unless therapists have explored their own conscious and unconscious cultural bias and racism, then it may be very unhelpful for them to take on a client from a different culture. Therapists also need an awareness of the client’s systems of belief, and the kind of myths and symbols, both personal and universal, that are familiar to them.

“One of the benchmarks of great communicators is their ability to listen not just to what’s being said, but to what’s not being said as well. They listen between the lines.”

Listening between the lines is a beautifully symbolic way of describing what it means to really hear another person. The phrase combines ‘listening to the music behind the words’ and ‘reading between the lines.’

- Myths that sometimes appear in therapy

The Phoenix Myth.

Phoenix – Kuang Xü. 1922. Wikioo.

Phoenix – Kuang Xü. 1922. Wikioo.

“You have risen from the ashes before. The only way to survive, ” he said, “is to believe you always will.”

Samantha Shannon, The Song Rising

The myth of the phoenix rising from the ashes offers a vivid example of courage, rebirth and renewal. It appears in several different cultures, always with the story of this special bird, which lives a long time, building her nest of twigs and spices. She then deliberately sets fire to her nest, engulfing herself in flames. In time, out of the ashes that remain, there arises a new phoenix, reborn and rejuvenated.

This myth may be brought into therapy, by client or therapist, depending on the therapeutic approach, when it seems to resonate with a client’s personal situation. It is as if the messages of this phoenix myth are:

“Your scars are evidence of your resilience. You survived difficulties in the past, you can do so again now.”

“Have hope for the future. The world can be productive and beautiful again. The possibility of new growth is within you.”

Phoenix – Katsushika Hokusai. Wikioo

Phoenix – Katsushika Hokusai. Wikioo

“We all have a heritage and history of being gutted, and yet remember this especially … we have also, of necessity, perfected the knack of resurrection.

Over and over again we have been the living proof that that which has been exiled, lost, or foundered – can be restored to life again. This is as true and sturdy a prognosis for the destroyed worlds around us as it was for our own once mortally wounded selves.”

Do Not Lose Heart, We Were Made for These Times ©2001, 2016, by Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Ph.D.

Phoenix-like, energy and strength may emerge from the ashes of adversity, revealing transformation, hope, and a kind of rebirth.

The therapeutic process, enriched by such powerful myths and symbols, can help us to work through our pain, and to face the existential issues that trouble us all. It can enable us to see ourselves and the world differently, to soften the ‘hard edges’ of our troubles, past and present.

Therapy can offer us renewal and recovery, the chance to live our lives more fully, the freedom to develop new hopes and dreams for the future. The story of the phoenix also involves a lesson in letting go, of past relationships, behaviour patterns, ways of thinking.

“We must always change, renew, rejuvenate ourselves; otherwise, we harden.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

The Icarus Myth

Another popular myth is that of Icarus, which a client* brought into therapy. This is the story of a young man, Icarus, who was imprisoned with his father, Daedalus.

The father made his son some wax wings so that he could escape their prison. In spite of warnings to the contrary, Icarus flew too near the sun, and his wings melted, resulting in him falling into the ocean and drowning.

Thomas Hawk. Icarus Making Trial of His Wings. Flickr

Thomas Hawk. Icarus Making Trial of His Wings. Flickr

“Never regret thy fall, O Icarus of the fearless flight, For the greatest tragedy of them all Is never to feel the burning light.”

Oscar Wilde

The client who recounted this myth in therapy had been in business, doing well, and then took an enormous financial gamble that ultimately failed. They lost everything. The client themselves had become aware that the Icarus story felt relevant to their personal struggle and retelling this story to me enabled them to talk symbolically about their own painful life events.

The client had felt some pressure, linked to past experience, to ‘fly to great heights’ at work. Their younger brother was a great success and received much parental endorsement.

We explored this feeling of pressure and where it had come from in the past, enabling him to consider being more individuated and to focus on self-determination.

We also looked at what Icarus- and the client- could learn from their experience. Another way of interpreting the myth is, instead of focussing on the story as an example of failure, we could admire and praise the courage and success he had in risking flying at all. This is the message behind Wilde’s quotation, above. The client, unlike Icarus, had a second chance to rebuild their life.

Clients so often bring dreams and stories into therapy. Depending on the therapeutic approach, therapists may or may not introduce myths themselves; in all cases, it is important that the therapist is aware of symbolic language and can pick up the cues beneath the words.

Therapists need to be able to detect every nuance, hidden meaning, symbolic reference, implication and ambiguity in the other’s words. For this they need an advanced form of understanding and comprehension in relation to what they hear, developing refined and sensitive ways of thinking about another’s words to help the client gain insight into themselves.

This will enable us to hear what is, perhaps, not expressed directly, but hinted at or implied through metaphor, symbol and myth.

Being able to think in this way, the therapist can help the client connect their issues to wider, more universal themes, so that they may feel less isolated or different.

Myths and symbols help to give life meaning, allowing a different viewpoint and enabling deep insights, which can be healing and transformative. They can also help us to create harmony between the unconscious and the conscious and to gain some understanding of emotions that are difficult to fully comprehend or verbalise.

“By a symbol I do not mean an allegory or a sign, but an image that describes in the best possible way the dimly discerned nature of the spirit. A symbol does not define or explain; it points beyond itself to a meaning that is darkly divined yet still beyond our grasp, and cannot be adequately expressed in the familiar words of our language.”

Carl Jung

Departing Souls. Bob. Flickr.

Departing Souls. Bob. Flickr.

“The soul speaks in images.”

James Hillman

*Permission was gained for all client material to be shared.

© Linda Berman

Again very engaging and full facts

LikeLike

Aah thanks again for your comment!

LikeLike

great understanding of symbolic thinking

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike