- Change and growth

Talking People. Lajos Kolozsváry.(1871–1937) Wikimedia Commons

Talking People. Lajos Kolozsváry.(1871–1937) Wikimedia Commons

Both people and language live and die… and in the space between they grow, and change. In the first part of this post, I highlight the links between human beings and their language, focussing on change and growth.

I also frequently draw comparisons between humans, language and trees, and I include several images of, and quotations about, these majestic, living structures. This is to emphasise how language- and people- have many similarities to trees; I show that we can learn much from their innate wisdom and interconnectedness.

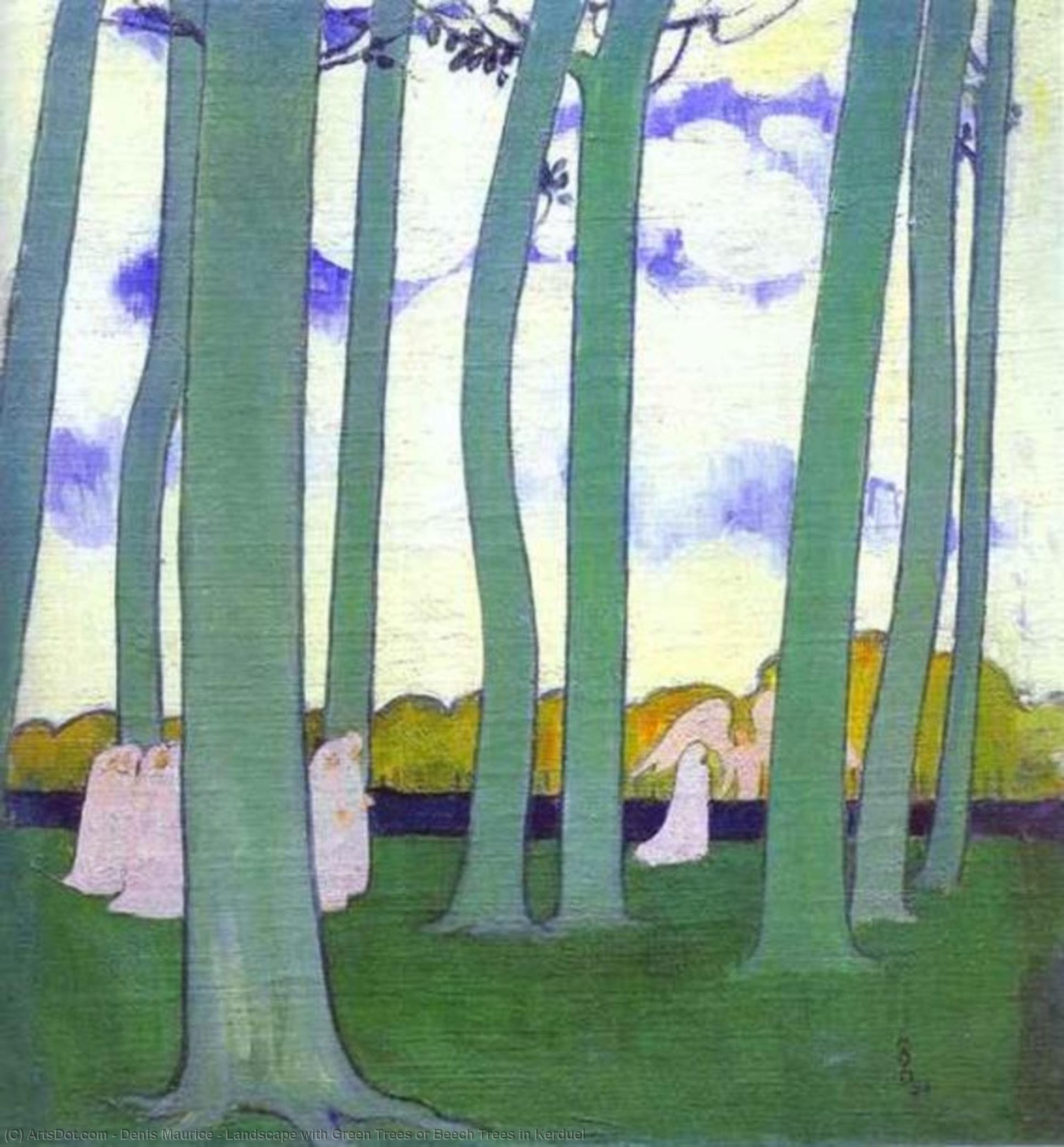

Landscape with Green Trees or Beech Trees in Kerduel – Denis Maurice. 1893. Wikioo.

Landscape with Green Trees or Beech Trees in Kerduel – Denis Maurice. 1893. Wikioo.

We can even show connections between therapy and trees, in that trees grow and develop gradually, slowly, imperceptibly, becoming steadily stronger to cope with the storms of life. In therapy, too, the client will make small changes over time, sometimes hardly noticeable, but subtly contributing to the gradual development of their hidden, inner strength.

This helps them to face life’s uncertainties and difficulties. In therapy, there is a need to establish a solid foundation, strong ‘roots’ and a firm anchor in terms of a good, trusting and stable therapeutic relationship.

“Therapy is a lot like growing a tree. For the first few years there appears to be no major growth, but by the third year, after the roots have established themselves and can support the trunk, the tree shoots upward.”

Catherine Gildiner

A tree’s life, its existence, is intricately connected to ours, reflective of and irretrievably linked to our own growth, both physical and psychological. Trees, as they weather storms, lose parts of themselves, and they grow new branches and leaves to compensate for their losses.

Whilst we cannot grow new limbs, we can grow psychologically and make up for the losses we experience. We can move forward in life, find new ways of being creative, such as having children, working, innovating.

Our lives in many ways reflect several different forms of nature, for we are part of one big, interconnected world and we can learn much from others.

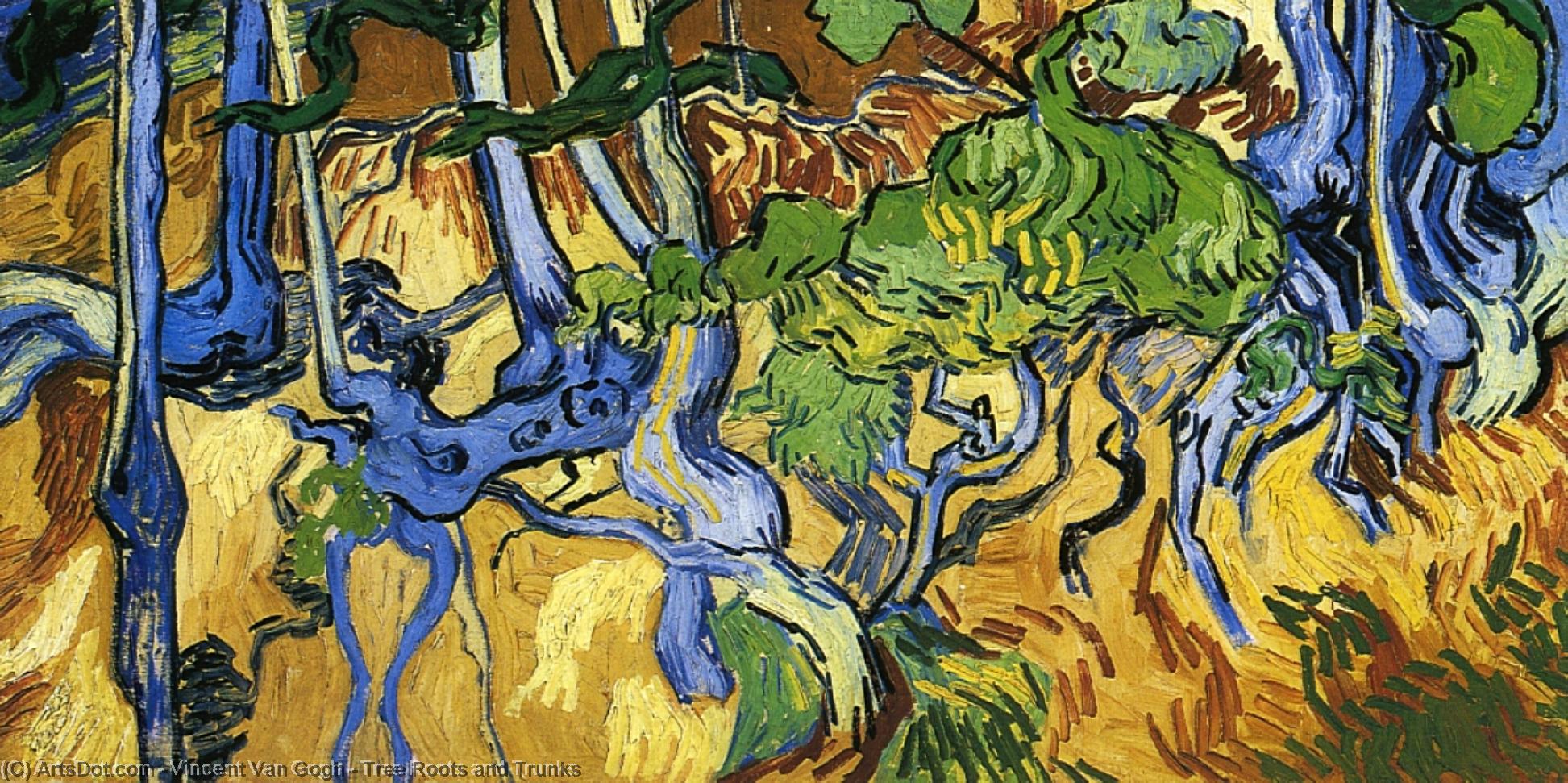

Tree Roots and Trunks – Vincent Van Gogh. Wikioo

“The ancient rhythms of the earth have insinuated themselves into the rhythms of the human heart. The earth is not outside us; it is within: the clay from where the tree of the body grows.”

John O’Donohue

Trees can mirror our own existence in this world, in which they play a crucial part. Through trees, we can glimpse reflections of humanity: renewal, hope, empowerment, resilience and wisdom. Somehow, they are quietly knowing, and they have much to teach us.

Many writers, as well as artists, have felt this kinship with trees:

Trees in the Moonlight. Carl Julius von Leypold. 1824. Wikimedia Commons

‘The sun was already declining and each of the trees held a premonition of night.’

E.M. Forster

“Storms break branches, not roots.”

African proverb

“Be like a tree and let the dead leaves drop.”

Rumi

“But down deep, at the molecular heart of life we’re essentially identical to trees.”

Carl Sagan

“This oak tree and me, we’re made of the same stuff.”

Carl Sagan

Like us, trees suffer trauma and are wounded, and like us, they may survive and bear the scars, growing and developing, maybe emerging even stronger.

Whilst some might decay or die, trees are resilient and strong and can recover from difficult times. This is where trees can give us hope, of renewal and regeneration.

“For it is the young tree grown out of the old root which shall illuminate what the old tree has been in its wonders.’

Jacob Boehem

“All tall trees are wise, according to the West African teacher Malidoma Somé, because their movement is imperceptible, the connection between above and below so firm, their physical presence so generously useful.”

James Hillman

- Some connections between trees and language…

The Mulberry Tree by Vincent van Gogh. 1889. Wikimedia Commons

“Language is a living thing. We can feel it changing. Parts of it become old: they drop off and are forgotten. New pieces bud out, spread into leaves, and become big branches, proliferating.”

Gilbert Highet

This quotation powerfully describes the links between trees and language. Language, too, is a living entity, with a life of its own. We use metaphorical language connected with trees in order to describe, illuminate and understand human situations, such as ‘family trees,’ ‘tree of life,’ ‘roots’ of human problems and support systems, interconnections and social links.

We often plant a tree to commemorate a lost person, or bury someone beneath a tree, so that their remains can ‘become’ an intrinsic part of that tree. Further, we talk of ‘branching out,’ and ‘the tree of knowledge;’ we also describe people as ‘being grounded.’

Like language, trees connect us with the past, where their roots are deeply embedded, and their new growth and outstretched branches offer us hope for our future. Language, too, ‘branches out’ into sentences and clauses, it ‘cross-pollinates,’ as it borrows from other languages, and expands and evolves. There are also ‘syntax trees,’ visual representations of the grammatical structure of a sentence.

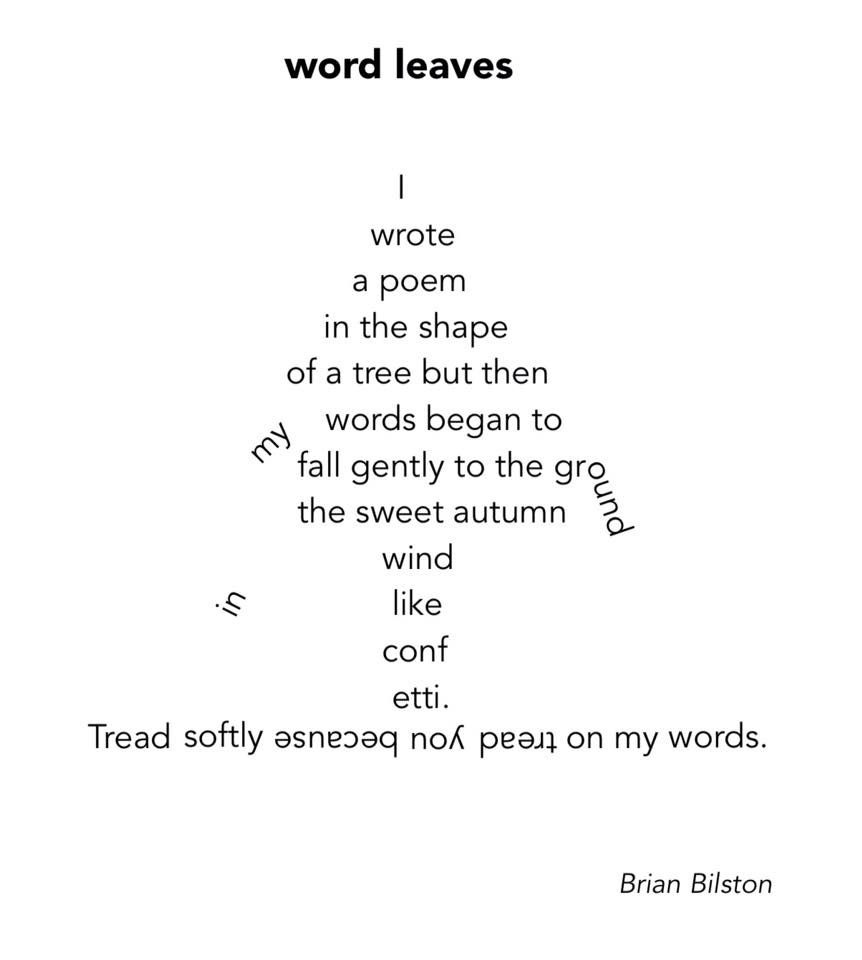

The innovative poet Brian Bilston uses the image of words tumbling down like leaves falling from a tree in a beautiful poetic and graphic way:

- Language and change

Cows Near Dieppe. Paul Gauguin. 1885. Wikioo

Cows Near Dieppe. Paul Gauguin. 1885. Wikioo

“The living language is like a cow-path: it is the creation of the cows themselves, who, having created it, follow it or depart from it according to their whims or their needs. From daily use, the path undergoes change. A cow is under no obligation to stay.”

E.B White

As language loses aspects of itself as the years pass, words become lost, forgotten, outdated. Sometimes the word survives, but its form changes, like tree branches that become lopped or twisted with time.

The words in the quote above ‘a cow is under no obligation to stay,’ powerfully reflect the situation of words and language; they remind us that language is certainly not fixed, nor does it have any duty to anyone to remain unchanging. Words can ‘wander off’ down any path they, or we, want them to…

For example, the word ‘defo’ has now entered the English dictionary, as a result of people using it informally in its shorter form, often in texts. This is a colloquialism for ‘definitely.’ (“You are defo going the wrong way.”)

New words take the place of older ones; this happens as people develop, as technology expands and new discoveries and innovative ideas take over old, worn-out ways of thinking.

“Our language is the reflection of ourselves.

A language is an exact reflection of the character and growth of its speakers”Cesar Chavez.

Many people feel that language should be protected, defended from change and the ‘whim’ of people who want to use new words and new forms of speech, pronunciation and grammar. In fact, an organisation was founded in France to do exactly this…

- Trying to stop change: the founding of L’Académie française

Paris, France. Institute de France (Académie française)Wikimedia Commons

In 1635, L’Académie française was established by Cardinal Richelieu. Its aim was to ‘maintain and preserve the purity of the French language.’

Characterised by extreme formality, the Académie still produces an official French dictionary and functions as an authority on the French language, aiming to regulate spelling, vocabulary and grammar.

I can remember learning about this at school in the 60’s; the teacher delivered the lesson in a serious and strict tone, without a hint of doubt in her voice that this was not a noble and worthwhile aim.

However, this organisation has today been described as ‘a largely inert, ceremonial government body:’

“The process of ‘preservation’ necessitates near-clinical conditions; items must be kept airtight, hermetically sealed. Preservation is not simply an act of protection or maintenance, but rather one of enforced stagnancy. Applying such a constrictive principle to language —an entity that is perpetually evolving—thus renders the Académie’s mission oppressive, near despotic. Attempting to maintain the version of the French language that was standardised in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in today’s modern, globalised, multicultural landscape is entirely unnatural, and can only be achieved by the kind of linguistic authoritarianism that the Académie proliferates.”

Trying to stop language change can be a futile mission. Can we ever actually ‘preserve’ a language? Attempting to do this surely reflects some people’s attempts to prevent change generally in life, to keep things rigid and immutable.

Whilst preserving parts of the past is important, in order that we have a sense of history and can learn from it, if we try to live in the past, to keep all the old ways, we will, inevitably, become stagnant and be left behind by the passage of time. Many people come to therapy in order to rid themselves of ‘stuck,’ old ways of thinking in life in general.

Very little remains the same in life and change can bring fresh thoughts and ideas. Changes in language, in vocabulary and grammar, reflect human life in all its richness and variety.

In this regard, I am reminded of an experience in my own life which goes back (a long way) to when I was studying English Language and Literature at university. In a small first year tutorial group, we were discussing language change. The tutor told us that language reflects people, and it is people that change the language. The dictionary merely records societal and linguistic changes; it certainly does not have ultimate authority over language.

This may seem a small, obvious piece of learning all these years later, but as a young person having grown up in a rather narrow, authoritarian culture, it was, actually, life-changing for me, for it heralded the beginning of my interest in human change and in psychotherapy.

I had always been instructed to regard the dictionary (and human forms of authority!) as the supreme, unchangeable and unquestionable leader in terms of spelling and meaning, and here I was being shown a different view.

Now, this new information felt explosive, rebellious, subversive, exciting. It was a lesson that was full of creative potential in my own life. It signified a sea-change in my ways of thinking.

If I had ever expressed a different view as a young person, I was told ‘everyone in the army is out of step but you.’ Suddenly, I was liberated from the emotions this had engendered in me, from the intense feelings of shame and foolishness around thinking differently. Now I began to generalise from this new, freeing and permission-giving experience, and to realise that I had some authority of my own and the right to my own opinions.

I did not always have to ‘go and look everything up’ and consult some authoritative tome. I could begin to think for myself. There were no absolutes, no ‘right’ interpretations of the world and its meanings.

Having been raised in an atmosphere of utter respect for the correctness and authority of books, this was mind-blowing for me. I needed to relearn, and this relearning represented a real change and a real awakening. I began to explore with considerable passion how language changes and the human reasons behind this.

Like us, language is influenced by different ways of thinking, and it absorbs words and phrases from other languages. This helps it grow and develop, infusing it with new, much-needed energy and enabling modernity and relevance in our growing and expanding world.

“A living language is like a man suffering incessantly from small haemorrhages, and what it needs above all else is constant transactions of new blood from other tongues. The day the gates go up, that day it begins to die.”

H. L. Mencken

“The only living language is the language in which we think and have our being.”

Antonio Machado

- Dead languages

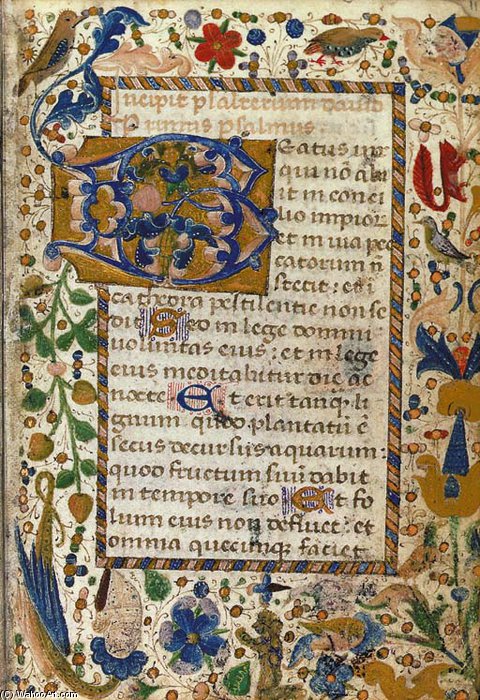

Psalter, In Latin, Illuminated Manuscript On Vellum – Vincent Clare. Wikioo

“The only languages which do not change are dead ones.”

David Crystal

There are many reasons for a language to become dead or extinct.

Languages die when there is no-one left to speak them or to choose to speak them. Whilst dead languages, such as Latin, Old English, Old Norse and Old High German may be unused today, their legacies in relation to our current forms of language is invaluable. Whilst these dead tongues cannot change, their strong influences can still be traced today in modern languages, of which they are the forerunners.

Extinct languages, however, such as Slovincian, a West Slavic language, do not have such a legacy, and there are few traces left of them. Often, such extinct languages have never had a written form.

Like trees, our living languages need, and have, histories and roots. They reveal the impact of these influences in their current, living forms. We still use many Latin phrases in our everyday speech, such as ‘ bona fide’ and ‘vice versa.’ Old Norse gave us ‘Thursday’ (from ‘Thor’s Day’), ‘skirt,’ ‘cake,’ ‘anger’ and ‘knife,’ and Old French contributed words like ‘surgeon,’ ‘jeopardy,’ and ‘cuisine.’

Next Tuesday, in part 2 of this post, I shall be exploring the ideas of eminent linguist Professor David Crystal; the post will focus especially on the effect of the internet and texting on language and language change. I also highlight issues of judgement, and the disapproval of many at the prospect of change and development, in language and in life.

© Linda Berman

Fascinating! Well, at least I find it fascinating. As an English teacher, one of the best courses I had at Washburn University was Origin of the English Language, after a brief start, we focused on Chaucer and Canterbury Tales. Then on to Shakespeare, showing the changes in our language. In teaching, my students learned Pidgin English,for fun and the memorization of the Prologue in Chaucerian language. Decades of students on FB lcontinue reminding me that they can still repeat the Prologue and have taught their children!. Finally we were able to understand why Shakespearian language is so difficult for students. We actually had quite a lot of fun with how our language continues changing, not just over centuries, but even over a few years at a time.

LikeLike

So interesting, Janet! Thanks for your comments- I too find the development of English fun – and so fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person